One Mutation Away From The Next Global Pandemic: Fall 2025 Update On H5N1

Is Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Going To Start Spreading In People This Year?

Last winter, 2024-25 I predicted on my social media platform that we were about two years (which would include next winter as well) or less from the virus developing human to human transmission capacity.

It’s a big prediction to make, and I hope that I am wrong, but with as little as one to three mutations in a notoriously mutagenic virus, person to person spread of H5N1 has really just become a matter of “when” not “if”.

That said, it is difficult to predict the mutational leaps a virus may or may not make. So as we head into the winter of 2025-26 I felt like it was a good time to update everyone on my thinking about this virus. I am still not certain when H5N1 will being spreading between people, but what I can say is that we are incredibly close to having a second pandemic in 5 years become a reality.

The reason I believe we are closer than ever is that H5N1 is only one to three mutations away from developing the capacity for human-to-human transmission. Well, really only one mutation, but the additional 2 or so mutations would make it spread even faster, and some of those mutations have already been detected in the wild.

Typically, when highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses make the leap to people, they come with greater transmissibility than a typical influenza and greater pandemic causing potential.

The United States is not prepared to face another pandemic, especially not one where the current mortality rate is up to 50% (likely to drop, but still may be higher than SARS-CoV-2). Political will is also ensuring a lack of preparedness by defunding surveillance, testing, and research supporting rapid development of a H5N1 vaccine that could be rapidly produced, much like the COVID-19 vaccine.

Which Mutations Have To Occur To Touch-Off The Next Pandemic?

The most important barrier is the virus’s preference for binding to avian (bird) sialic acid receptors which are different enough from the human sialic acid receptor that it typically prevents inter-species infection.

However, influenza can and does mutate to overcome this barrier and has in several past pandemics. While earlier H5N1 strains typically required three or more mutations to achieve this, the bovine-derived dominant H5N1 clade in North America 2.3.4.4b has demonstrated this switch with just one change. Researchers found in the laboratory that Q226L could lead to human cell spread. Although I have seen some articles dismiss this as being ‘done in a laboratory’ I would like to remind those other authors that this is how the company Regeneron predicted the next sets of SARS-CoV-2 mutations in 2020 with tremendous accuracy.

But what does ‘one change’ actually mean?

Sometimes an amino acid change (in this case from glutamine (Q) to leucine (L)) requires several nucleotide (DNA or RNA, RNA in this case) changes, however, in this case it only requires one point mutation in the genetic code of the virus to change the Q at position 226 to L. To make maters worse, the influenza virus does not have a good ‘proof reading’ mechanism, leading to one of the highest mutation rates, even among other RNA viruses.

Other mutations that may cause issues can be found at sites in the polymerase genes (PB2 E627K and D701N) and are likely to further increase replication efficiency and adaptation in mammalian hosts. Some currently circulating viruses already possess one or more of these mutations.

Mutation Isn’t The Only Way Influenza Can Adapt

Genetic reassortment is a process in which influenza viruses exchange gene segments when two different strains infect the same host cell. Influenza viruses have segmented genomes, typically eight separate RNA segments, enabling this mix-and-match exchange. During co-infection of a cell, segments from both parental viruses can be packaged together into new viral particles, producing “progeny” with mixed genetic material. These reassorted viruses can display novel traits such as altered host range, transmissibility, sometimes leading to dramatic shifts in virus behavior. Historical influenza pandemics, including 1957, 1968, and 2009 arose through reassortment events that combined genes from animal and human strains. This is a powerful evolutionary mechanism for influenza viruses and a significant concern for public health as it can allow an influenza virus to emerge suddenly with new properties.

In 2024 in Cambodia at least 25 H5N1 infections were reported in the winter, and genetic analysis identified a reassortment of two influenza viruses creating a new virus that contains the surface genes from 2.3.2.1e and internal genes from 2.3.4.4b. There this new strain has mostly replaced older clades in local poultry and represents the principal cause of recent human spillover infections. All cases were a result of direct contact with ill or recently deceased backyard poultry. Unfortunately the case fatality rates remained as high as prior H5N1 outbreaks, at about 50 percent. Identified genetic markers (such as PB2 E627K) were consistent with mammalian adaptation, but sustained human-to-human transmission was not reported.

Is The United States Likely To Be The Epicenter?

It’s difficult to predict when and where a virus will develop mutations that allow it to spread rapidly person to person. However, repeated human infections due to repeated close human - host animal contact increase the chances a virus may develop a beneficial (for the virus) mutation and begin to spread human to human.

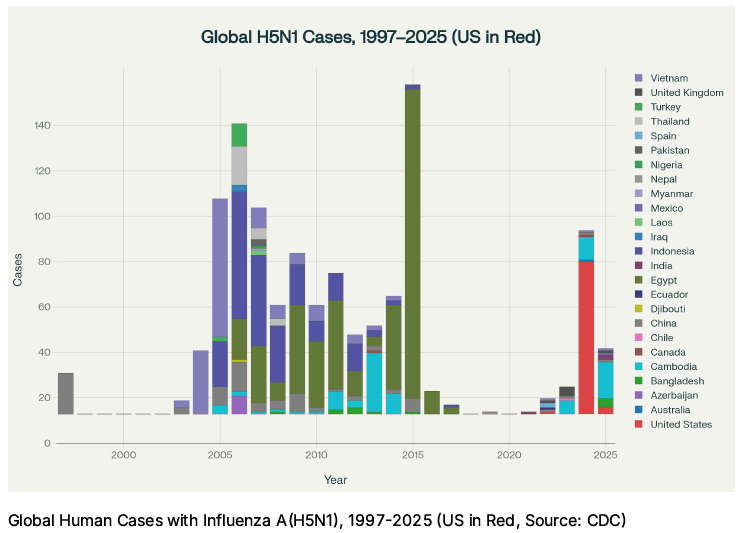

Last winter 70 cases were reported in the United States, with the vast majority of them being tracked back to direct animal exposure, typically dairy cattle.

The below graph shows the location of human infections with H5N1 since 1997.

Some indication of potential human-to-human transmission has been seen in people without direct animal exposure (but exposure to an infected person) developing antibodies against H5N1. When your immune system ‘sees’ a virus it will develop antibodies to combat it, though none of these cases were reported to be severe and in many cases the person did not have symptoms.

If the strong northern hemisphere dominance of cases in the United States starting in the 2024-25 influenza season persists, it becomes more likely that the United States will be the epicenter of the next global pandemic. Note: The 2025 cases on this graph represent the end of last year’s influenza season and no cases of H5N1 have been reported for the 2025-2026 influenza season as of this writing.

Furthermore, good public health measures such as surveillance, education, rapid testing, and PPE (masks, gloves, gowns) distribution can rapidly reduce spread of a virus. However, there has been an erosion of common sense public health measures in the United States, making it more likely that if mutations in the virus occur here, significant sustained H5N1 spread could also start in the United States.

The Southern Hemisphere Remains H5N1 Free

Despite Australia suffering through a bad flu season this winter, no region in the southern hemisphere has officially reported H5N1 infections in humans or animals during the 2025 winter. Surveillance updates from Australia, New Zealand, southern Africa, and South American countries indicated that highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 was not detected through the peak winter flu season. While seasonal influenza viruses circulated at moderate to high levels in some regions, H5N1 outbreaks remained confined to the northern hemisphere and some regions near the equator. Both national and international organizations, including the WHO and local ministries, confirmed that southern hemisphere surveillance efforts, did not identify any new or confirmed H5N1 activity among people or animals during the 2025 winter.

The lack of any significant spread of H5N1 in the southern hemisphere during the 2025 winter is good news on the pandemic front. The fewer viral infections, the fewer chances a virus has to mutate.

Aside From Being More Deadly, H5N1 Shows An Increased Risk Of Brain Infection

Sometimes it’s difficult to encourage people to pay attention when everything is labeled as being “just the flu”.

For those of us who have had (tested positive) Influenza infection, we know that even as young and health adults you may become incredibly sick. Unfortunately, the strain of H5N1 in wide circulation appears to also be able to infect brain tissue, a new-ish trick for influenza and something we won’t know the implications of until we see wide-spread human infection.

Recent research has shown that certain H5N1 virus strains possess marked neurotropic properties, meaning the virus can invade and damage neural tissue. Experiments have demonstrated that H5N1 can cause fatal neurological disease in mammals, including rodents, cats, and marine mammals. In fact, many veterinarians have reported barn cats from areas with infected cattle dying from seizures, not respiratory issues, while infected with H5N1. Research has shown that H5N1 infection can cause encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, and neuronal cell death, with affected mammals displaying neurologic signs like ataxia (loss of balance) and convulsions.

The virus is capable of reaching the central nervous system through the olfactory nerve and can induce persistent inflammatory injury in brain regions, including the loss of dopaminergic neurons similar to SARS-CoV-2 which leads to brain fog and depression.

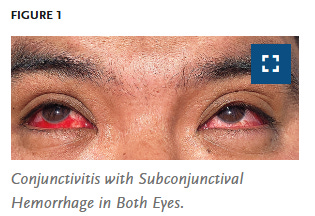

Indeed in humans, per this New England Journal of Medicine Report, conjunctivitis, which can have a neurological connection, is a common symptom even in mild cases where the virus is still not well adapted to infecting human cells.

Though most human H5N1 cases currently involve severe respiratory disease, the presence of neuroinvasive behavior in animal models raises serious concerns. While H5N1 is not efficiently transmitted among humans at present, t

he demonstrated ability to infect brain tissue and ongoing mammalian adaptation suggest that future mutations could substantially increase morbidity and mortality should the virus acquire human-to-human transmissibility.

What Can You Do?

If you haven’t gotten your flu shot this year, please consider doing so very soon and as always discuss it with your doctor if you have any questions. If H5N1 does reach pandemic status this year, the H1N1 in the current flu shot may offer some protection. I detail this in a prior introduction to H5N1 research here.

Continue to wear a mask to protect yourself. For example, I always wear one when flying and despite always testing at least twice when I’ve felt sick, I have not yet had COVID-19.

Wash your hands (influenza lasts longer on surfaces than SARS-CoV-2) and be careful not to touch your eyes, nose, or mouth between touching a high-touch surface (hand rail, door handle to a building etc.) and washing your hands. There is some recent evidence that high-salt nasal rinses may reduce symptoms and the number of sick days, just be sure to always use distilled water. If you feel sick, stay home to prevent spread to others and discuss the best course of action with your physician.

And finally, share this article with anyone who you think it may help.

References

Science (2024). A single mutation in bovine influenza H5N1 hemagglutinin switches receptor-binding preference. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt0180

Respiratory Therapy (2024). Bird Flu Mutation Could Increase Human Transmission Risk. https://respiratory-therapy.com/disorders-diseases/infectious-diseases/influenza/bird-flu-mutation-increase-human-transmission-risk/

Phys.org (2025). Analysis reveals H5N1 mutations linked to human adaptive potential. https://phys.org/news/2025-08-analysis-reveals-h5n1-mutations-linked.html

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology (2025). Emerging H5N1 mutations (PB2-D701N, PB2-E627K, HA-S110N, Q226L): Cross-species threats. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12333729/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Global Summary of Recent Human Cases of H5N1 Bird Flu (August 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/h5n1-summary-08042025.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation - CDC (September 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/index.html

World Health Organization: Avian Influenza A(H5N1) - Cambodia (July 2025). https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON575

CIDRAP: Cambodia announces 15th human H5N1 infection of the year (September 2025). https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/cambodia-announces-15th-human-h5n1-infection-year

BlueDot: The curious case of avian influenza in Cambodia (July 2025). https://bluedot.global/the-curious-case-of-avian-influenza-in-cambodia/

GlobalBioDefense: Cambodia Reports Surge in Human Infections with Avian Influenza A(H5N1) (July 2025). https://globalbiodefense.com/2025/07/08/cambodia-reports-surge-in-human-infections-with-avian-influenza-ah5n1/

Cleveland Clinic: Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): H5N1, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment (September 2025). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22401-bird-flu

Nature: Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b genotype exhibits neurotropic behavior and heightened threat (June 2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-60407-y

Science News: Bird flu has been invading the brains of mammals. Here’s why (July 2024). https://www.sciencenews.org/article/bird-mammal-brain-outbreak-influenza

PNAS: Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus can enter the central nervous system (August 2009). https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0900096106

New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries: Surveillance and planning for HPAI (bird flu) | NZ Government (March 2025). https://www.mpi.govt.nz/biosecurity/pest-and-disease-threats-to-new-zealand/animal-disease-threats-to-new-zealand/high-pathogenicity-avian-influenza/surveillance-and-planning-for-avian-influenza/

PMC: Avian Influenza Virus Surveillance Across New Zealand and Its Pacific Neighbors (March 2025). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11949760/

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance: Everything you need to know about bird flu (April 2025). https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/everything-you-need-know-about-bird-flu

Nature: Circumpolar spread of avian influenza H5N1 to southern Indian Ocean islands (September 2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-64297-y